What can be learned from Jurassic Park phylogeny? Hopefully, this article will clarify most of the uncertainty and popular misconceptions surrounding the animals shown on screen.

The article covers the current consensus and explains the uncertainties of the relationships of the prehistoric animals featured in the Jurassic Park and Jurassic World films, both to each other and other animals.

A host of new animals are set to appear in the upcoming Jurassic World: Dominion, so I may have to do a follow-up at some point!

I covered what exactly a dinosaur is in my last article which covered every Jurassic Park dinosaur using modern science. To recap, a dinosaur is defined specifically as any animal descended from the last common ancestor of Iguanodon, Megalosaurus, and Plateosaurus.

This definition comes from the PhyloCode, the International Code of Phylogenetic Nomenclature. These are formal rules for naming groups of animals, called clades, which finally saw publication in January 2019.

These three animals represent the three major groups of dinosaurs, but before we discuss this let us cover the non-dinosaurs.

Non-Dinosaur Relationships

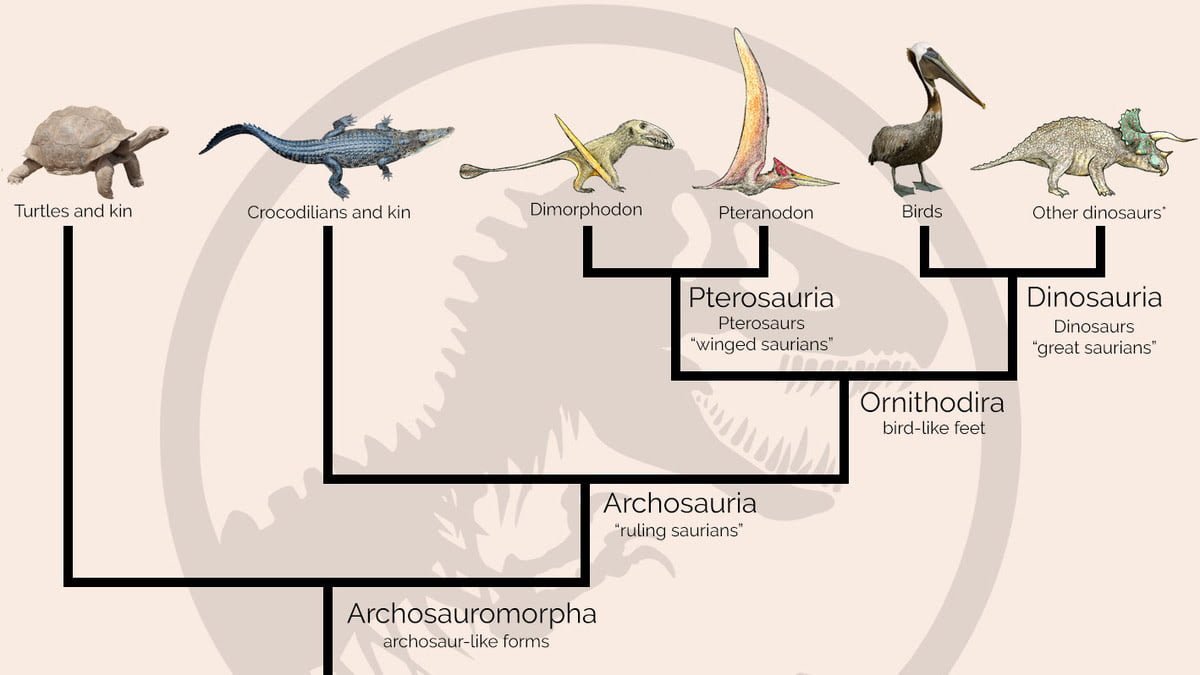

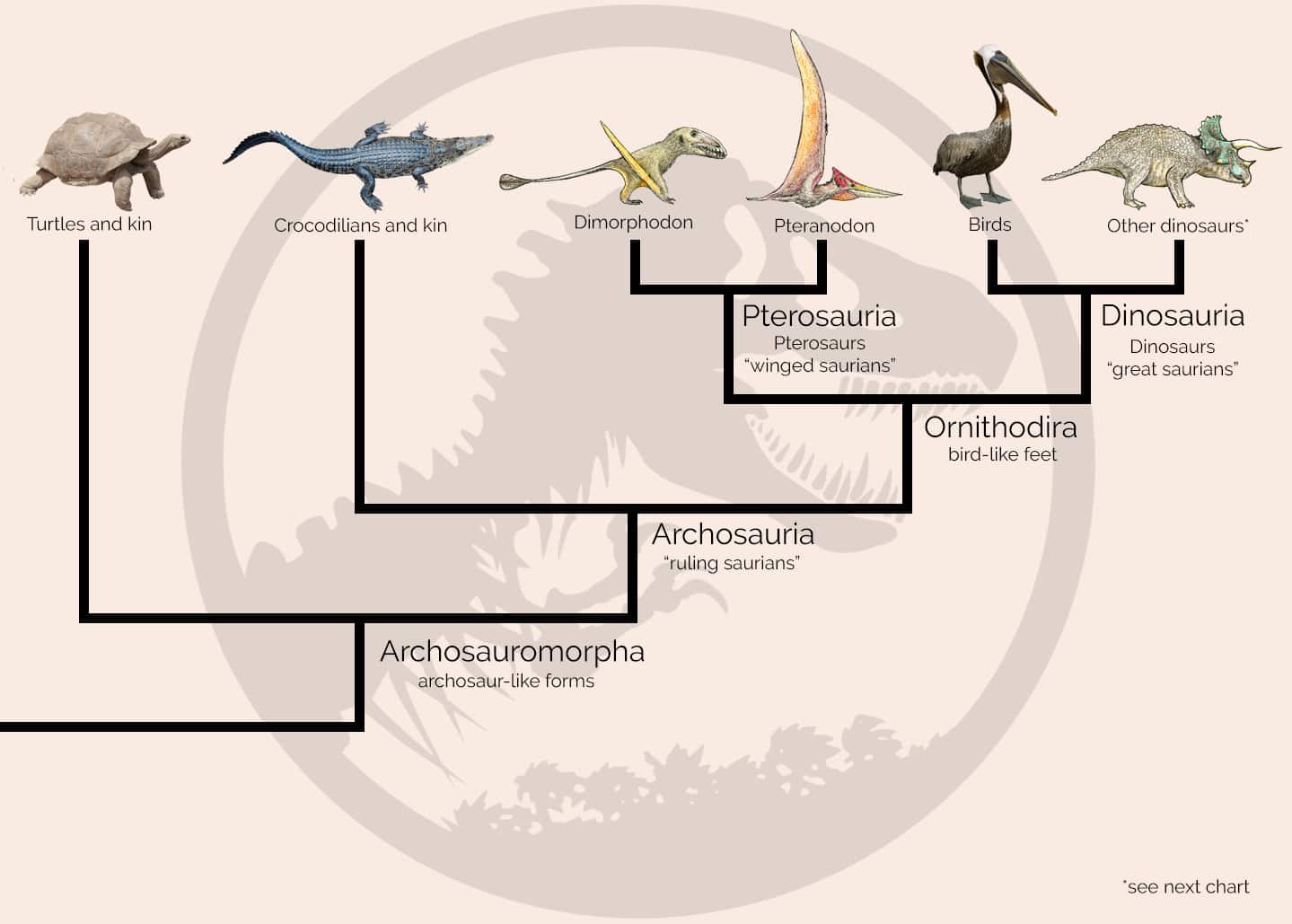

Of the animals cloned from fossil DNA in the films, not many represent non-dinosaurs. So far only 2 pterosaurs and 1 mosasaur have appeared. More prehistoric animals unrelated to dinosaurs are set to appear in Dominion, but that is a story for another day.

Pterosaurs

Often called “pterodactyls” by the public, pterosaurs are a group that, much like dinosaurs, appeared in the Triassic period and rose to prominence in the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Unlike dinosaurs, which survive today in the form of birds, pterosaurs were completely wiped out by the end-Cretaceous mass extinction event.

Throughout their reign, pterosaurs achieved many forms, including tiny bat-like insect hunters, divers, filter feeders, and finally giant predators that became the largest animals to ever fly. The Jurassic Park and World films offer only a tiny glimpse at this diversity, featuring 3 different versions of the long-crested Pteranodon and the small primitive pterosaur Dimorphodon.

I don’t generally think it is all that egregious when people refer to pterosaurs as dinosaurs. It is wrong, but they are one of the closest relatives of dinosaurs that we know of currently.

These two groups, along with the crocodilians and their relatives form a larger group called archosaurs, or the ruling reptiles. Crocodilians and birds are the only surviving archosaurs.

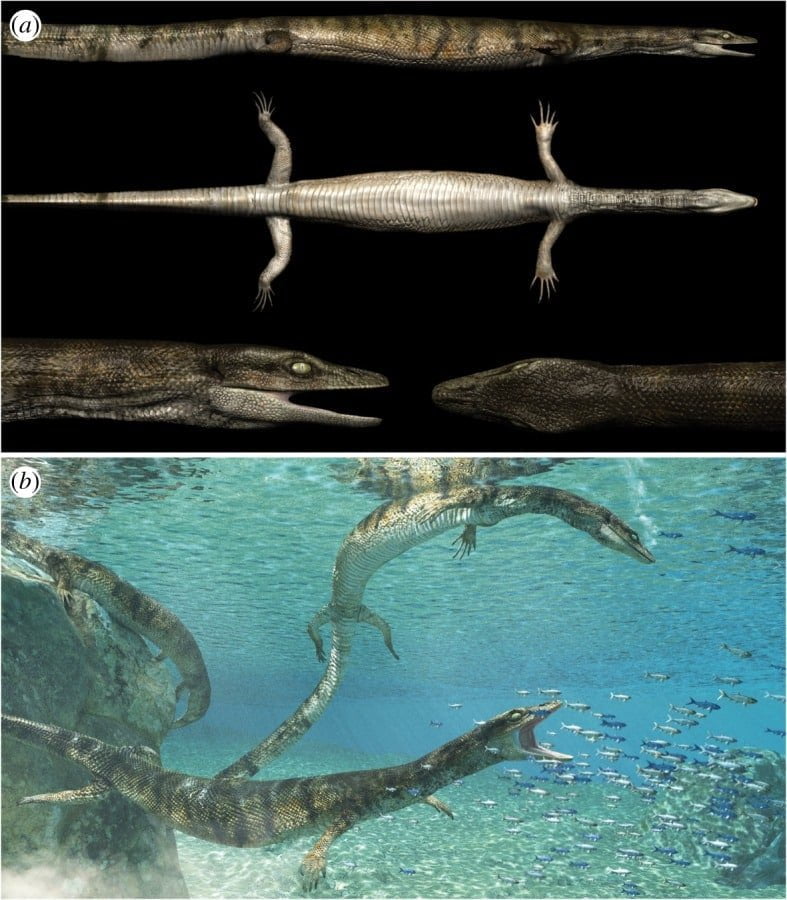

Mosasaurs

Let’s quickly cover the other cloned extinct animal from Jurassic World, the mosasaur. You may remember this as the giant whale-like reptile that eats a dangling shark in the trailer. In reality, this animal was much smaller and less crocodilian. Check my previous article for more details on that.

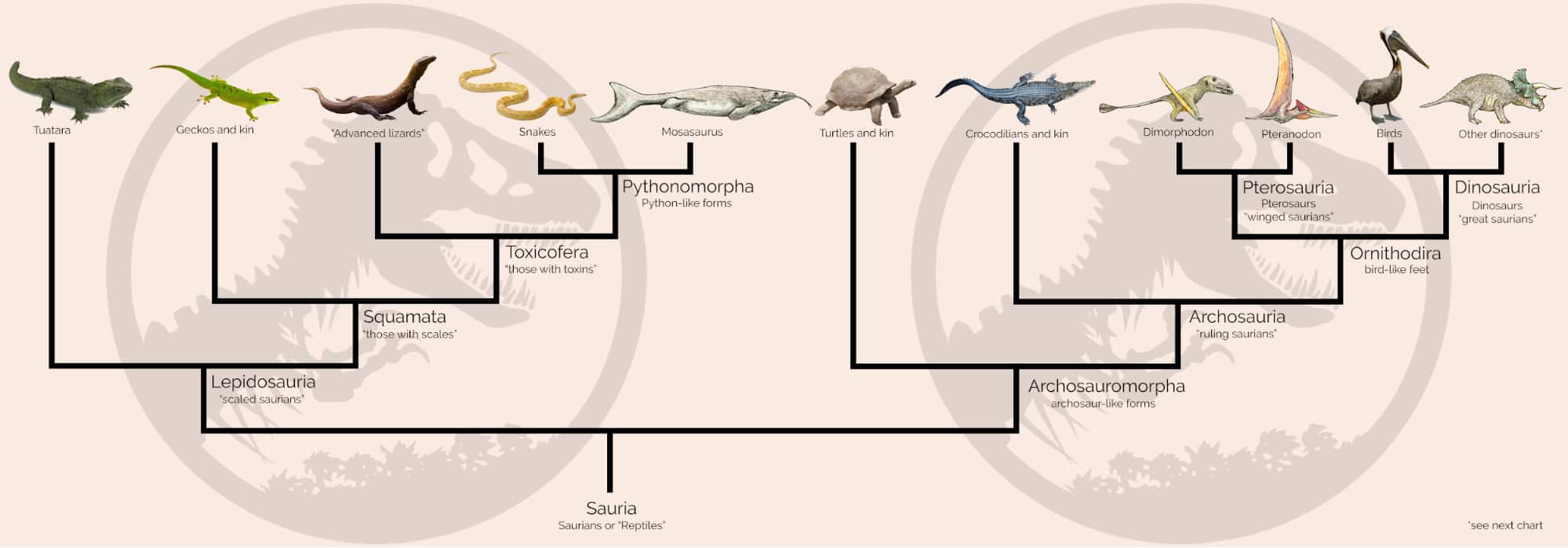

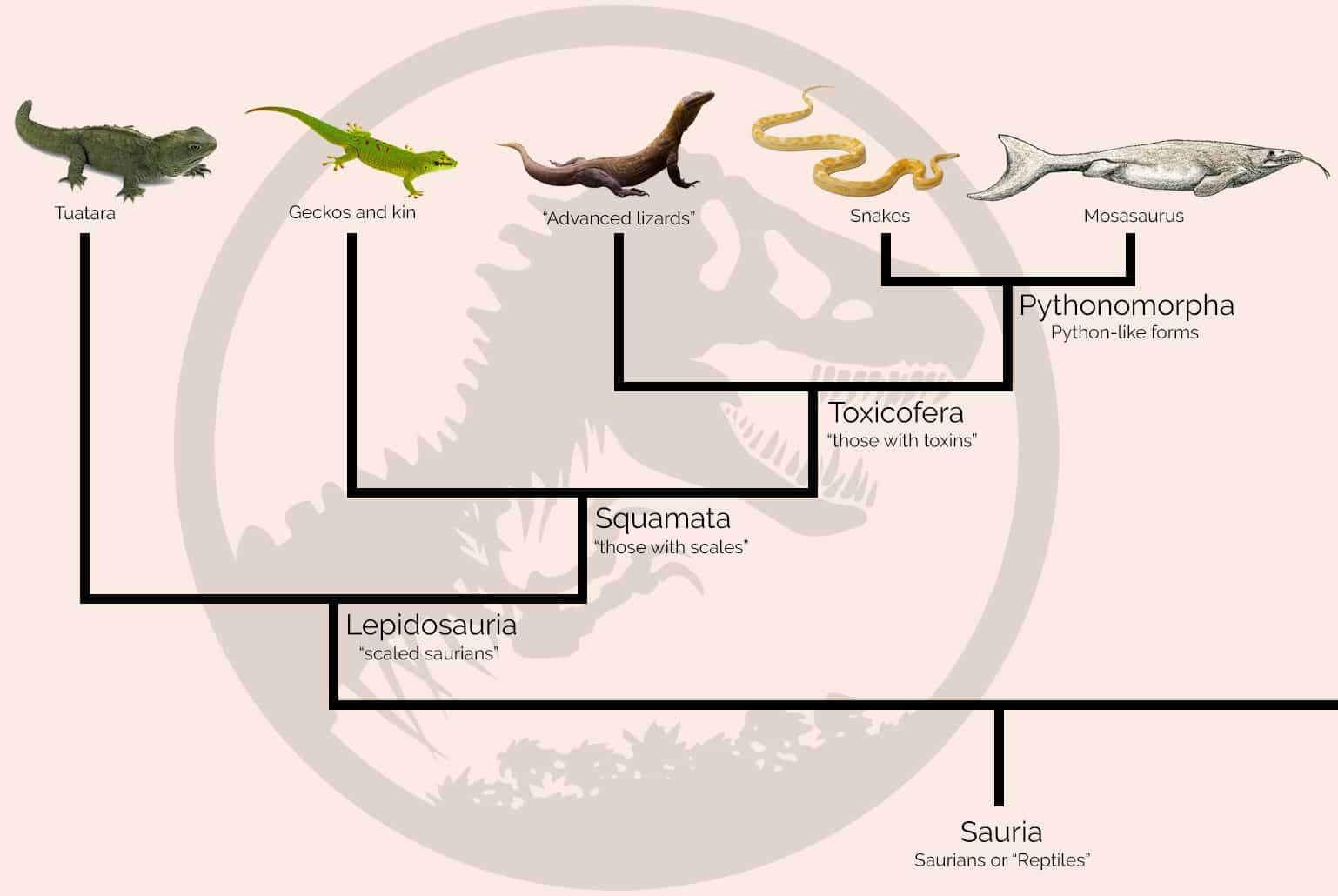

Mosasaurs were a group of large marine reptiles that lived in the Cretaceous and again, met their end with the great bolide impact. While it has to be constantly emphasized that Mesozoic dinosaurs and even pterosaurs are more closely related to birds than any other living reptile group, mosasaurs are lizards. As in, actual lizards under all definitions, and thus, have nothing to do with dinosaurs.

While I noted above that calling pterosaurs “dinosaurs” is an easy mistake as they are very closely related, this is not the case for mosasaurs. Lizards and snakes, including mosasaurs, are about as far from dinosaurs as you can get while still being reptiles.

We already learned that pterosaurs, dinosaurs, and crocodilians are part of a group called the archosaurs. The archosaurs represent one major branch of reptiles. The lizards, snakes, and enigmatic tuatara from New Zealand, form the tip of the other major branch, called the lepidosaurs, the scaled reptiles.

One additional interesting point on mosasaurs: some recent research popping up over the last decade – including analysis of relationships using both fossils and genomes, as well as some newly discovered “transitional forms” are indicating that mosasaurs may be the closest living relatives of snakes, rather than any other group of lizards.

This is ongoing research and should be considered tentative for now.

Dinosaur Relationships

Now we’ve touched on what a dinosaur is and isn’t, let’s cover how actual dinosaurs are related to one another.

The first point to be aware of are the three major groups of dinosaur:

- Ornithischia: means “bird-hipped,” but ironically does not include birds. This group includes most of the beaked herbivores like Triceratops and Iguanodon.

- Sauropodomorpha: means “saurian feet” and includes the giant long-necked herbivores such as Brachiosaurus and their ancestors like Plateosaurus.

- Theropoda: means “beast feet” and includes almost all known carnivorous dinosaurs, such as Megalosaurus and Tyrannosaurus, some secondary herbivores and omnivores like Gallimimus, as well as birds and their closest relatives.

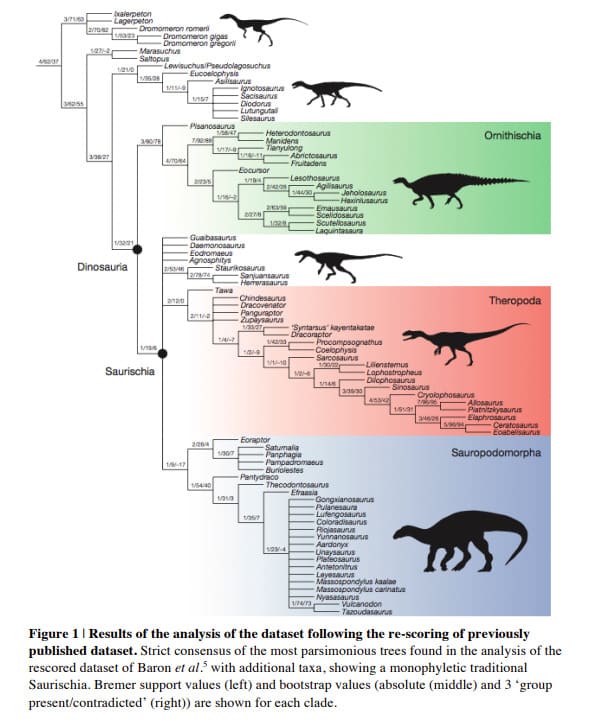

Traditionally it has been accepted that these 3 higher groups are arranged with sauropodomorphs and theropods forming a group together called Saurischia, lizard-hips, and Ornithischia as the outgroup.

The Ornithoscelida Conundrum

Sometime around 2017, you may have heard that there was a major shakeup in dinosaur relationships. This was in response to a paper analyzing the relationships of the earliest dinosaurs, which found a different arrangement for the three major groups.

They found theropods to group with Ornithischians instead of sauropodomorphs, in a group called Ornithoscelida, or bird-limbs. However, this study was quickly questioned by multiple research groups.

This is all a bit beyond the scope of this article, but this pair of videos by the Your Dinosaurs Are Wrong YouTube team gives an excellent and comprehensive overview. You can see these videos below:

I will be following the traditional Ornithischia/Saurischia split in the rest of this article, but the jury is still out on this issue.

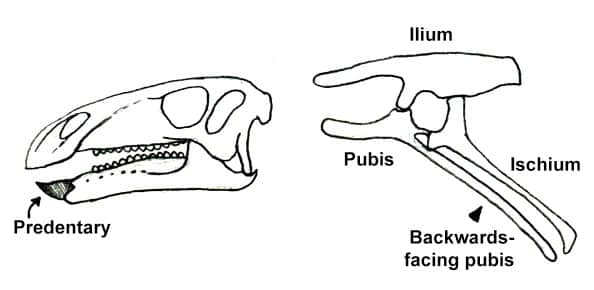

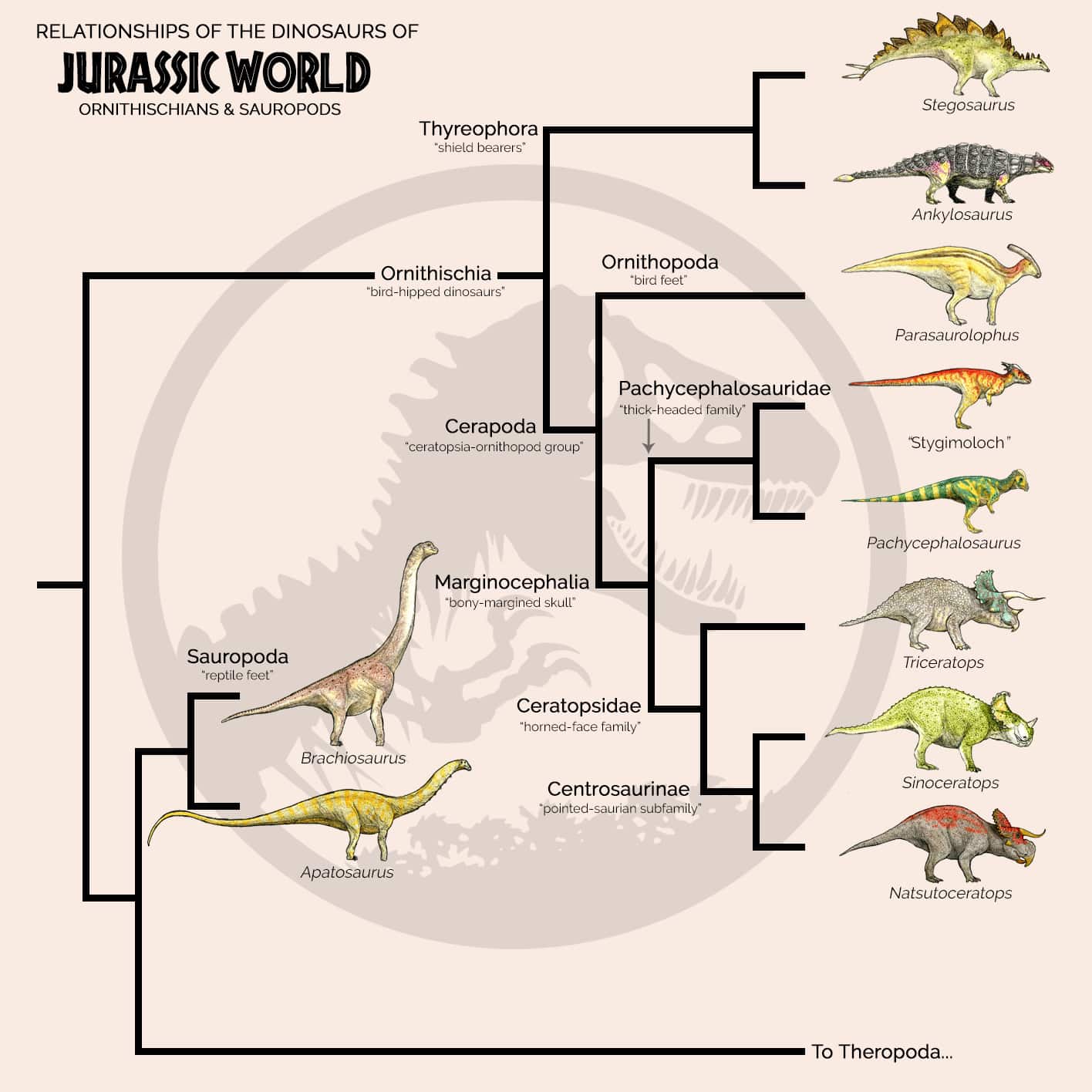

Ornithischia

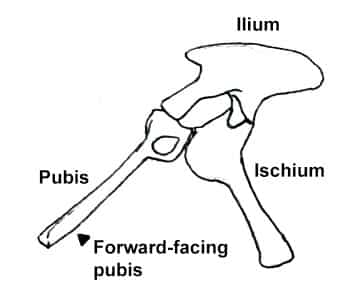

So what are the ornithischians? This group is defined primarily by the orientation of the hip bones, which point backward. This condition was developed independently in birds, hence the name, which means bird-hipped. Birds are confoundingly, a type of Saurischian dinosaur.

Birds probably developed this hip structure as an adaptation to a shift from thigh-driven to knee-driven walking, while ornithischians may have evolved this condition to make room for a long herbivorous gut.

When speaking to laypeople, I refer to the Ornithischians as the beaked herbivores, which cover most bases. This also references another shared character of the Ornithischians: the predentary bone.

This is a unique bone at the top of the lower jaw that forms the bottom half of the beak. Herbivorous theropods that independently developed beaks, like Gallimimus and some birds, do not have a true predentary bone.

So finally we can get back to Jurassic World: who from this film series belongs in the Ornithischia?

One of the earliest groups to split off from Ornithischia are the Thyreophora, meaning “shield bearers.” From this name, you might have guessed that the armored Ankylosaurus belongs to this group, but so does the famous roofed-saurian Stegosaurus.

Stegosaurs and ankylosaurs are each other’s closest relatives. Both rose to prominence in the Jurassic period. Ankylosaurs stayed quite small during this period, while stegosaurs became moderate-to-large-sized herbivores in their ecosystems.

The end of the Jurassic saw the stegosaurs mostly die out, with only a couple of species petering out in the Early Cretaceous. The ankylosaurs, however, got through this extinction unscathed and evolved into much larger and more diverse forms which lasted right up until the end of the Age of Dinosaurs, including Ankylosaurus itself.

Next, we have the duck-billed Parasaurolophus, which is remarkably the only member of its larger group, Ornithopoda, to appear in the Jurassic World films so far. Jurassic Park III did show its close relative Corythosaurus, and Iguanodon appears in the YouTube prologue for Jurassic World Dominion.

The ornithopods first appeared in the Jurassic, where they occupied many small-to-medium herbivore roles. Perhaps something like the antelope of the dinosaur world.

Hypsilophodon is a famous animal in this ecomorph. In the Cretaceous, this group began to rapidly diversify, which eventually saw the rise of Iguanodon and the duck-billed dinosaurs known as hadrosaurids.

These would be the dominant large herbivores of the Cretaceous era. This dominance may have had something to do with the processing power of their chewing apparatus. Chewing teeth allowed them to extract resources from a wide variety of plants as opposed to other herbivores that simply swallowed vegetation without chewing.

I’m somewhat bitter that the entirety of the important ornithopods get only one representative while the small family Pachycephalosauridae gets two. So far, all pachycephalosaur remains come from the Late Cretaceous of North America and Eastern Asia, which were connected at the time.

These animals are famous for their thick domed heads. The Jurassic World films feature Pachycephalosaurus, the largest of the family, and Stygimoloch, which may be just another species of Pachycephalosaurus. See the previous article for more discussion of this topic.

Despite looking kind of like thick hypsilophodontids with domed heads, pachycephalosaurids are closer to the ceratopsians. These two groups together are called Marginocephalia. This name refers to a bony ridge on the margin of the skull that they share.

Ceratopsians are the most well-represented Ornithischian group in Jurassic World, with three so far. Triceratops is the touchstone here. Sinoceratops and Nasutoceratops are admirably more obscure pulls, though again I might have preferred some more ornithischian diversity rather than two more ceratopsids.

As is a common theme with Ornithischians, ceratopsians first appear as very small herbivores in the Jurassic of Asia, and later diversify and spread across the Northern Hemisphere during the Cretaceous.

The large, horned forms, including all three of Jurassic World’s ceratopsians, are in the family Ceratopsidae, which was almost entirely a phenomenon of Late Cretaceous North America. So far, the only species known from outside North America is Sinoceratops, which lived in China.

Saurischia and Sauropodomorpha

The other major herbivorous dinosaur group is the sauropodomorphs. The Jurassic World films feature Apatosaurus and Brachiosaurus from this group.

Sauropodomorphs are the first of the two Saurischian dinosaur groups. While the Ornithischians discussed above are defined by their backward-pointing pubis, the Saurischian pubis ancestrally points forwards.

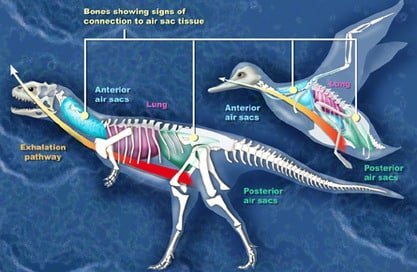

Another unique feature of Saurischians is their hollow bones. You may be aware of the hollow bones of birds. Hollow bones help them to fly and allow their air-sac system to infiltrate the skeleton.

These features are inherited from their Saurischian ancestors. This may also have allowed sauropods to reach such enormous sizes. More information on how hollow bones allow for enormous size can be found in our other article: Why Were Prehistoric Animals so Large?

Sauropodomorphs get their start in the Triassic as small omnivores or even carnivores but slowly get larger and more inclined towards herbivory as that period continues. Plateosaurus is the most famous example of this transition, as it is quite large, somewhat long-necked, and herbivorous, but still bipedal.

In the Jurassic, this group became the dominant herbivores on land and the largest terrestrial animals to have ever existed. These are where the recognizable forms appear, with their four legs, long necks, and counterbalancing tails.

Brontosaurus and Diplodocus are further examples. In the Cretaceous, another group appeared, the titanosaurs, which remain dominant in the Southern Hemisphere until the end of the Cretaceous. They are less common on the northern continents but do still make it to the end-Cretaceous extinction event. Dreadnoughtus, which appears in the Jurassic World Dominion movie and prologue, is a Late Cretaceous titanosaur.

Theropoda

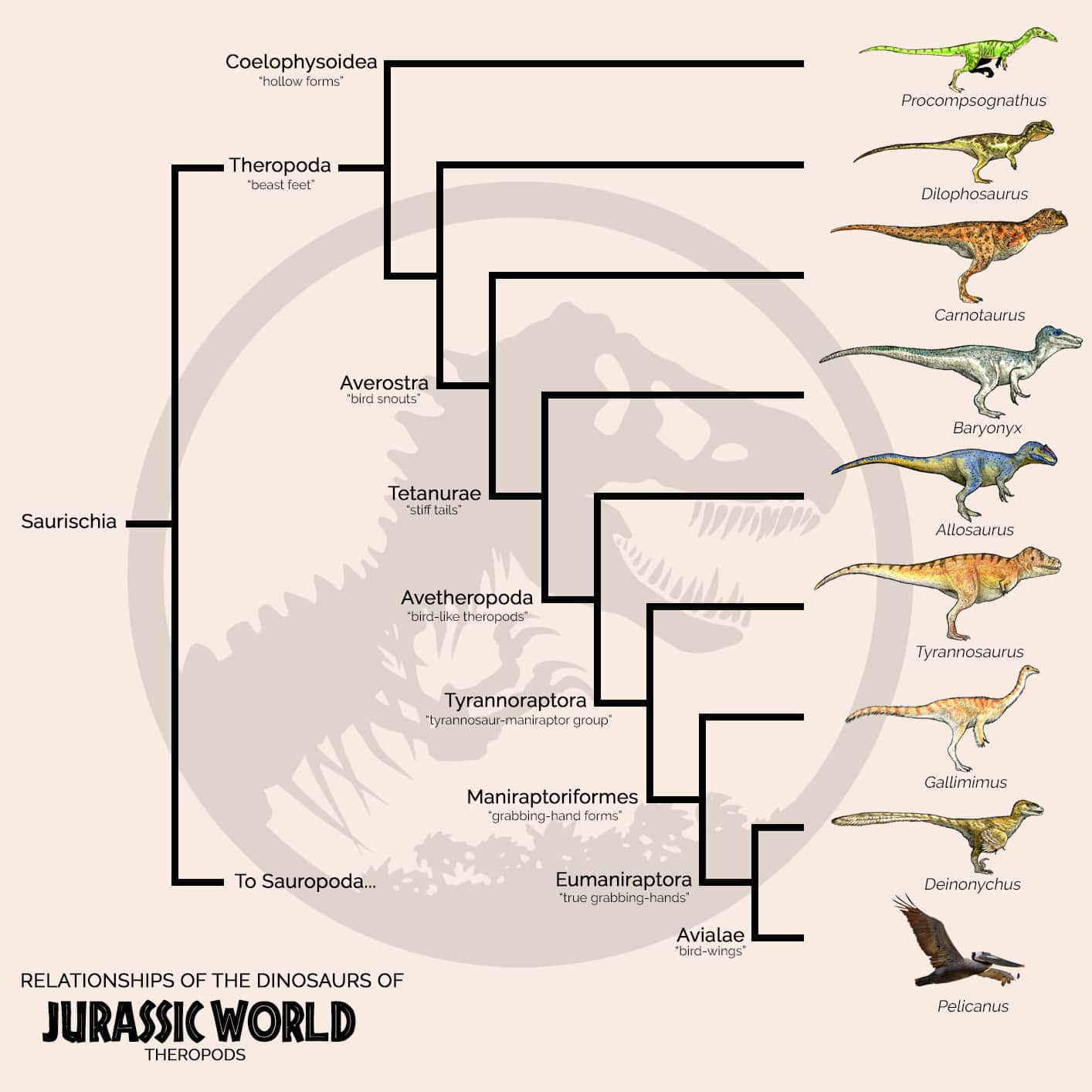

The majority of the dinosaurs in the Jurassic World films, especially Jurassic World Fallen Kingdom, are in the final group: Theropoda. This group includes all the featured carnivores, as well as the fast-running omnivore Gallimimus.

The first Jurassic Park book introduced the series to the early theropods Dilophosaurus and Procompsognathus.

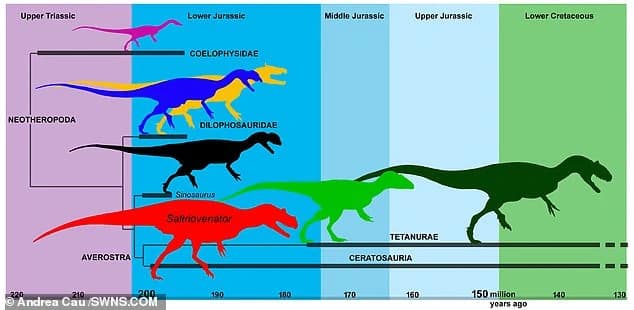

Procompsognathus was a tiny carnivore from the Upper Triassic belonging to the Coelophysidae. They can be seen swarming over Peter Stormare in The Lost World. Coelophysidae became widespread in the earliest days of the dinosaurs but disappeared sometime in the Lower Jurassic.

Around the time this group vanished, Dilophosaurus emerged as one of the earliest large carnivores. It was not the venom-spitting pipsqueak shown in the films.

Dilophosaurus was once considered a coelophysoid as well. Since the late 2000s, it has consistently been found to be closer to more advanced theropods.

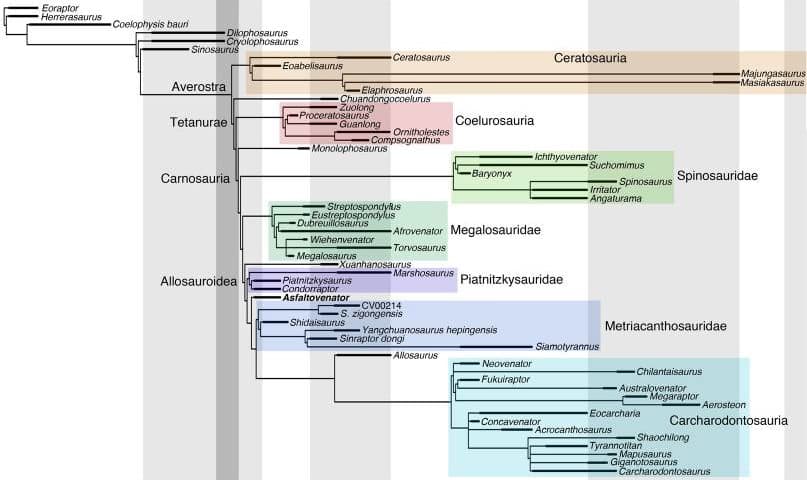

In the early Jurassic, the averostran theropods appeared. These theropods were closer to birds than Dilophosaurs and split into several major groups. The first of these were the Ceratosauria.

Much like the sauropods, this group thrived worldwide in the Jurassic but became extinct in the North during the Cretaceous. However, they continued to thrive on the Southern Continents until the end, eventually becoming the apex predators of places like South America.

One such animal was Carnotaurus, the horned predator featured in Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom. Another example is Ceratosaurus, which lived in the Late Jurassic alongside Brachiosaurus and Stegosaurus. It appears briefly in Jurassic Park 3 before being repelled by Spinosaurus dung.

The rest of Jurassic World’s theropods fall into the group Tetanurae, meaning stiff tails. This group gets a shout-out in Fallen Kingdom where it is mentioned that Blue the “Velociraptor” needs a blood transfusion from another member of the tetanurae. They end up taking blood from the T. rex.

Ignoring the fact that cross-species blood transfer can be very dangerous, why they chose a T. rex and not a much safer, and more closely related Gallimimus I do not understand.

Anyway, the first group to cover here are the spinosaurids. Fallen Kingdom features a Baryonyx and Jurassic Park 3 offers a Spinosaurus on steroids.

These curious animals emerged in the Early Cretaceous and obtained nearly worldwide distribution before going extinct as quickly as they appeared in the middle of the Late Cretaceous.

They seem to be related to the Megalosauridae from the Jurassic, which together form the Megalosauroidea. This group is either sister to or slightly more basal than the next group: the allosauroids.

Allosauroidea includes the famous Jurassic predator Allosaurus, as well as the Early Cretaceous family Carcharodontosauridae. Carcharodontosauridae includes some of the largest land carnivores ever.

One example is Giganotosaurus, featured in Dominion. The dinosaur Monolophosaurus, a smallish carnivore that appeared in the third season of Jurassic World: Camp Cretaceous, might be one of the earliest members of this group.

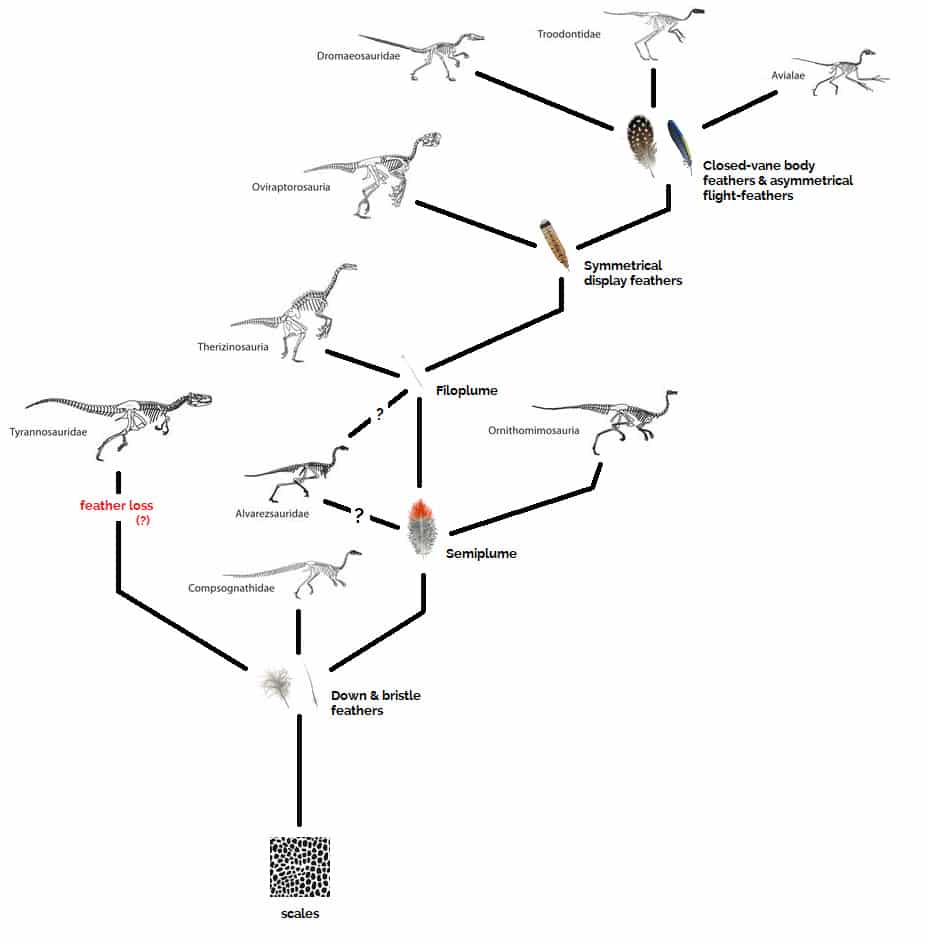

The remainder of the animals belong to the group Coelurosauria, the feathered dinosaurs. The origin of feathers is complicated and controversial, but Coelurosauria is where true feathers unambiguously related to modern bird feathers appear.

Remarkably for such a large and diverse group, only three coelurosaurs have been featured in the Jurassic Park franchise so far, all from the very first film. The biggest of this group is T. rex, which is a part of the Tyrannosauroidea, the earliest large group of coelurosaurs to appear.

Ancestrally, this group had downy feathers, but Tyrannosaurus itself may have lost them secondarily. See our other article to learn more about dinosaur feathers. This would not have been the case for the following taxa.

Gallimimus has had its bird-like qualities emphasized since the beginning. Grant states that they run “…just like a flock of birds evading a predator!” This makes sense, as Gallimimus comes from a family called the “bird mimics,” the ornithomimids. Indeed, mimic is right because it is less related to birds than some other famous dinosaurs like Oviraptor and Velociraptor.

Ornithomimids appeared in the Jurassic during the vast radiation of coelurosaurs and became some of the most dominant small herbivores throughout the Cretaceous. Velociraptor (or Deinonychus, see my previous article) belongs to the dromaeosaurids.

These are among the closest relatives to birds that existed. Indeed, dromaeosaurs possessed true modern-style feathers and wings, some small species seem to even be capable of flight to some extent.

Wrapping Up Jurassic Park Phylogeny

While it can be a confusing subject, I hope this article has provided clarity on the relationships between the animals featured in the Jurassic Park and Jurassic World movies. Next time you talk about these movies with friends, take a moment to share this article.

If you have further questions, please leave a comment and we will answer them as soon as possible. Again, if you haven’t read the Jurassic Park Dinosaurs article, check that out next.